About Acne

What is acne?

Acne, also known as acne vulgaris, is a very common inflammatory skin condition that is characterised by the appearance of spots (blackheads, whiteheads, pus-filled spots, red spots, nodules and cysts) on the skin. It varies from a few spots on the face, neck, chest or back to a more severe disease with widespread involvement that can cause significant scarring. Acne of all severity can have a big impact on self-confidence and mental health.

Acne usually starts at puberty (the reasons why we’ll cover below) when most of us will experience at least mild acne. Although many people’s acne will resolve in their late teens or early twenties, for many it can persist throughout much of their adult life and some people will also develop acne for the first time when they are older.

What does acne look like?

Acne affects skin with the highest number of follicles and oil glands which is why it most commonly appears on the face, back and upper chest – these are the areas of skin with the highest density of follicles and oil glands. When you have acne, you can develop any (or a combination) of these different types of spots on your skin:

- Whiteheads (closed comedones)

- Blackheads (open comedones)

- Pustules (pus-filled spots)

- Papules (red spots)

- Nodules / cysts (deeper, bigger, painful red spots)

We’ll go through each of these spots and what causes them in more detail below:

Whitehead

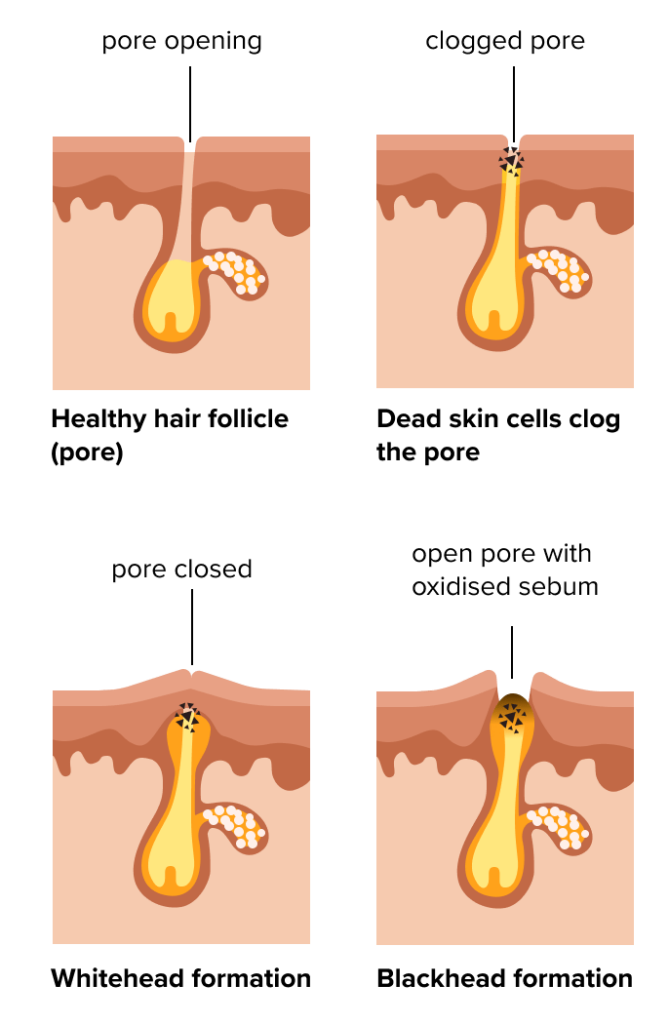

A whitehead is a small, raised, white or skin coloured spot that forms when excess oil and dead skin cells clog up the opening of a pore. The pore remains closed which is why it looks white or skin coloured and this is why we call them “closed comedones”.

Blackhead

A blackhead is a small, raised spot that appears black in the centre. It forms in the same way as a whitehead (a pore clogged with excess oil and skin cells) but this time the pore opening is widened. The black colour is not due to dirt as commonly assumed, rather it’s caused by a chemical reaction that occurs when the material blocking the pore combines with oxygen and turns black. The pore is widened in blackheads which is why we call them “open comedones”.

Pustule

Blocked pores provide an ideal environment for bacteria (that normally live on our skin) to grow and multiply. This can result in inflammation and the formation of a yellow spot (filled with pus) which is called a pustule.

Papule

The same process with bacteria and inflammation in the pore can cause a red spot without pus which we call a papule.

Nodule or cyst

Sometimes the inflammation in the pore can go deeper into the skin resulting in a lump under the skin that we call a nodule or a cyst. These are usually bigger and more painful than papules and are more likely to result in scarring if left untreated.

How common is acne?

Acne is very common and worldwide almost 1 in 10 people will have acne at any given time [1]. People of all ages get acne but it’s most common in teenagers where studies have found up to 90% of teenagers will develop acne at some stage [2]. Acne usually first appears around the onset of puberty when our oil glands start producing more oil [3]. Because girls tend to start puberty earlier than boys, acne normally affects girls earlier in their teenage years than boys [4]. When we become older teenagers and enter adulthood, the overall number of people affected with acne drops [3].

Most people who develop acne will have mild acne but for up to 1 in 5 people it will be moderate to severe [5] with men more likely to have severe acne [6].

Acne that develops after the teenage years is referred to as “adult acne” and this occurs more commonly in women. A study showed that 45% of women aged 21-30, 26% of women aged 31-40 years and 12% of women aged 41-50 years had adult acne [7].

What causes acne?

Acne is a disease of the follicle and oil-producing glands of the skin (also called sebaceous glands) and a number of processes underlie the condition. First the sebaceous glands produce too much oil (also called sebum), usually in response to messages received from sex hormones. This is one of the main reasons acne appears during puberty, when sex hormones are at their highest. This also explains why many females experience acne breakouts around the time of their period, which usually coincides with raised sex hormone levels. At the same time, the follicles become clogged up with dead skin cells that have become sticky and are not shed properly. These factors result in a buildup of oil and dead skin cells that clog pores (the openings of the follicle onto the outer skin) and result in the formation of blackheads and whiteheads.

The bacteria, cutibacterium acnes also plays a role in acne. This bacteria is found on most people’s skin without causing any issues however, in acne-prone skin the excess oil creates an environment where it leads to overgrowth of the bacteria triggering inflammation and leading to red, pus-filled spots.

Our genes are also thought to play a role in acne and studies have shown that you’re more likely to develop acne if your parents have also been affected [6]. It’s likely that many genes contribute to the development of acne but recent studies have found that specific genes (ones with key roles in determining how our cells respond to sex hormones) can contribute to more severe acne in some people [4].

Some underlying medical conditions are associated with the development of acne. For example, the condition polycystic ovarian syndrome (often referred to as PCOS) is a very common condition in females which results in abnormal sex hormone levels in the blood which in turn can lead to acne, excess hair growth (or loss), irregular periods and obesity (or difficulty losing weight).

Lifestyle factors have not been found to cause acne but can contribute to it. For example stress, diets high in sugars, lack of sleep and being overweight have all been linked to worsening of acne [6].

How is acne treated?

Topical treatments: (such as creams and gels) are usually the first choice for acne that is mild to moderate in severity. There are a few different active ingredients that have been used by dermatologists to treat acne for decades. These include ingredients such as benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, antibiotics (such as clindamycin and erythromycin), retinoids (such as adapalene, tretinoin, isotretinoin), azelaic acid and niacinamide. Topical treatments should be applied to the entire area affected by acne (not just individual spots). Irritation caused by topical treatments is relatively common and side-effects such as burning, redness and peeling are fairly common in the first few weeks of applying treatment. It is often advised that treatments should be introduced gradually (e.g. a couple of times a week) until the skin can tolerate daily application. Usually side effects settle after a few weeks.

Oral antibiotics: antibiotics such as tetracyclines and erythromycin are often given for moderate to severe acne. They are given for their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects and a course usually lasts between 8 and 12 weeks. Antibiotics are given in combination with a topical treatment as the antibiotics alone are not enough to tackle the underlying cause of acne.

Oral isotretinoin: this is a powerful and highly effective treatment for the most severe forms of acne and for most patients will clear acne long-term. However, it has the potential to cause a number of serious side effects and should only be prescribed under the supervision of a consultant dermatologist.

Skincare tips

Having a good skincare routine can help improve acne-prone skin and prevent further acne spots from developing. Here is what you should be doing:

- Wash twice a day and after sweating.

- Use your fingertips to apply a gentle cleanser with lukewarm water to your face twice a day and avoid cleansing your face with face cloths, brushes, scrubs or any mechanical cleansers containing micro globules as these can irritate your skin and make acne worse. Remove makeup before your cleansing step by double cleansing (doing the cleansing step twice) or using a micellar water.

- Be gentle with your skin. Use gentle products, such as those that are alcohol-free. Do not use products that irritate your skin, which may include astringents, toners and exfoliants. Dry, red skin makes acne appear worse.

- Try and avoid comedogenic skincare and makeup products as these will usually contain ingredients that are less likely to clog up your pores. This is particularly important when applying a moisturiser.

- Don’t pick, pop, or squeeze your spots as this usually will take longer to clear and you increase the risk of scarring and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

- Keep your hands away from your face. Touching your skin throughout the day can cause flare-ups.

- Protect yourself from the sun and always avoid tanning beds as UV light can worsen acne as well as post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Some acne medications such as Tretinoin and Lymecycline can also make your skin more sensitive to UV light meaning you’re more likely to burn. Please remember that UV light, and in particular tanning beds, increases your chances of developing the deadliest form of skin cancer called melanoma.

What are the complications from acne?

One of the biggest problems that results from acne is the formation of acne scarring. This is usually only seen in more severe forms of acne where the large, painful nodules form but can also result from smaller spots. Who goes on to develop scarring can also be related to your underlying genetics. Another key factor in scar development is how long you have acne for, with studies showing the longer you have acne, the more likely you are to have scarring [4].

There are different types of acne scars but most of them will result in indentations in your skin. Scarring can be very difficult to treat but there are options including laser treatments and chemical resurfacing and sometimes surgery can be helpful. The most important thing however is preventing the scarring from appearing in the first place and to do this it’s essential to treat your acne as early as possible.

Another complication of acne is the formation of brown marks/stains on the skin that we term post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). This is more common in darker skin types but can also occur in fairer skin types where it often leaves red marks on the skin, known as post-inflammatory erythema (PIE). PIH and PIE are often confused by people as scarring. The key difference is that PIH and PIE are flat marks on the skin that will usually fade over months once the acne is under control, whereas scarring usually results in much deeper changes in the skin that are usually permanent.

As a visible skin condition, acne of all severities can have a big impact on self-esteem, mental well-being and self-worth. Several studies have shown the negative impact acne can have on mental health and it’s been proven that people with acne are more likely to have anxiety and depression compared to those without acne [8].

For more expert information and support on acne, click this link http://www.acnesupport.org.uk/

References

- Vos, Theo, et al. “Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.” The lancet 380.9859 (2012): 2163-2196.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23245607/

- Stathakis, Voula, Monique Kilkenny, and Robin Marks. “Descriptive epidemiology of acne vulgaris in the community.” Australasian Journal of Dermatology 38.3(1997): 115-123.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9293656/

- Bhate, K., and H. C. Williams. “Epidemiology of acne vulgaris.” British Journal of Dermatology 168.3 (2013): 474-485.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23210645/

- Tan, Jerry KL, and K. Bhate. “A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne.”British Journal of Dermatology 172 (2015): 3-12.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25597339/

- Williams, Hywel C., Robert P. Dellavalle, and Sarah Garner. “Acne vulgaris.” TheLancet 379.9813 (2012): 361-372.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21880356/

- Heng, Anna Hwee Sing, and Fook Tim Chew. “Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris.” Scientific reports 10.1 (2020): 1-29.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32238884/

- Perkins, Alexis C., et al. “Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the lifespan.” Journal of Women’s Health 21.2 (2012): 223-230.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22171979/

- Zaenglein, Andrea L. “Acne vulgaris.” New England Journal of Medicine 379.14(2018): 1343-1352.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30281982/